"We Have a Bleeder!"... Hemophilia Explained

- Bryan Knowles

- Dec 15, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 17

Defining Hemophilia and Normal Hemostasis

Hemophilia (sometimes spelled haemophilia in the British style) is an inherited bleeding disorder characterized by impaired blood clot formation due to deficiency or dysfunction of specific coagulation factors.

There are several "types" of hemophilia: Type A, Type B, von Willibrand's, and others that may be either inherited or acquired.

Under normal circumstances, hemostasis (basically, the ability to stop bleeding once started) is a tightly regulated process involving platelet adhesion and aggregation followed by activation of the coagulation cascade, culminating in fibrin clot formation. In hemophilia, this cascade is disrupted, leading to delayed or inadequate clot stabilization. The result of hemophilia is a tendency toward prolonged bleeding, particularly into joints, muscles, and soft tissues, even in the absence of obvious trauma. Clearly, this is dangerous if not managed.

The Historical Understanding of Hemophilia

Hemophilia has been recognized for centuries, with early descriptions appearing in ancient legal and medical texts that noted familial bleeding tendencies among males. The condition gained particular historical prominence through European royal families, most notably the descendants of Queen Victoria, whose lineage disseminated hemophilia across several royal houses. Nineteenth-century physicians began to systematically describe the disorder, distinguishing it from other bleeding conditions. The twentieth century brought transformative insights with the identification of specific clotting factors, development of laboratory assays, and elucidation of X-linked inheritance. These advances shifted hemophilia from a mysterious familial curse to a scientifically defined disorder that can actually be treated (imagine that). See more on the history of hemophilia here.

The Coagulation Cascade and the Role of Clotting Factors

And here's where it gets complicated, but don't worry, most hemophilias will be common types. You don't need to memorize the entire coagulation cascade (for this anyway).

The coagulation system functions through a sequence of enzymatic reactions traditionally described as one of the three pathways: intrinsic, extrinsic, and common pathways.

Hemophilia primarily affects the intrinsic, in which factor VIII and factor IX play critical roles in amplifying thrombin generation. When these factors are deficient, thrombin production is insufficient, fibrin formation is delayed, and clots are unstable. This biochemical defect explains why bleeding in hemophilia is often delayed rather than immediate and why platelet counts and bleeding times may appear normal despite significant hemorrhagic risk.

Types A and B and von Willibrand's

Hemophilia A

Hemophilia A is the most common form of hemophilia and results from deficiency of coagulation factor VIII. It is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern, meaning it predominantly affects males, while females are typically carriers.

Clinical severity correlates with residual factor activity. Severe hemophilia A is marked by spontaneous joint and muscle bleeds, moderate disease presents with bleeding after minor trauma, and mild disease may not become apparent until surgery or significant injury. Recurrent hemarthroses, particularly in the knees, ankles, and elbows, can lead to chronic pain, synovial inflammation, and progressive joint destruction if not adequately treated.

Hemophilia B

Hemophilia B, historically known as Christmas disease, is caused by deficiency of coagulation factor IX and shares many clinical features with hemophilia A. It is also inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern and exhibits a similar spectrum of severity based on factor levels. Although clinically indistinguishable without laboratory testing, hemophilia B differs at the molecular level, with numerous identified mutations affecting factor IX synthesis or function. Recognition of this distinction is essential for appropriate therapeutic selection and genetic counseling.

Hemophilia B is most closely associated with the bleeding disorders of European royal families.

Von Willebrand Disease: The Most Common Inherited Bleeding Disorder

and Role of Von Willebrand Factor

Von Willebrand disease is an inherited, genetic bleeding disorder caused by quantitative or qualitative defects in von Willebrand factor, a plasma glycoprotein essential to normal hemostasis. Von Willebrand factor plays a dual role in coagulation: it mediates platelet adhesion to sites of vascular injury by binding to exposed subendothelial collagen, and it serves as a carrier protein for coagulation factor VIII, protecting it from premature degradation in circulation. Deficiency or dysfunction of von Willebrand factor therefore disrupts both primary hemostasis and, indirectly, secondary coagulation.

Pathophysiology of Bleeding in Von Willebrand Disease: In normal hemostasis, von Willebrand factor anchors platelets to damaged endothelium under conditions of high shear stress, such as in arterioles and capillaries. When von Willebrand factor is reduced or functionally abnormal, platelet adhesion is impaired, leading to prolonged mucocutaneous bleeding. In more severe forms, reduced stabilization of factor VIII results in secondary coagulation defects resembling mild hemophilia A. This dual mechanism explains the wide clinical spectrum of von Willebrand disease, ranging from mild bruising to significant surgical or postpartum hemorrhage.

Other Types: Rare and Acquired Forms of Hemophilia such as Autoimmune hemophilia

Beyond classic hemophilia A and B, rare inherited deficiencies of other coagulation factors can produce hemophilia-like bleeding disorders. Additionally, acquired hemophilia represents a distinct entity in which autoantibodies develop against factor VIII, leading to functional deficiency. This condition typically occurs in older adults or postpartum women and presents with sudden-onset severe bleeding in individuals with no prior bleeding history. Acquired hemophilia often manifests with extensive soft tissue bleeding and carries significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated.

Another subset of autoimmune disease is that in which antibodies attack the platelets. These disorders can cause very low platelet counts (<5) and thus cause danger to severe bleeds.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

The hallmark clinical feature of hemophilia is bleeding disproportionate to injury. Joint bleeding is particularly characteristic and, when recurrent, leads to hemophilic arthropathy with cartilage destruction, joint deformity, and impaired mobility. Muscle hematomas may cause nerve compression or compartment syndrome, while intracranial hemorrhage remains the most feared complication due to its potential lethality. Chronic pain, disability, and psychosocial burden are common long-term consequences, highlighting the disease’s impact beyond acute bleeding episodes.

Treatment of Hemophilia

The Past: Evolution of Hemophilia Therapies

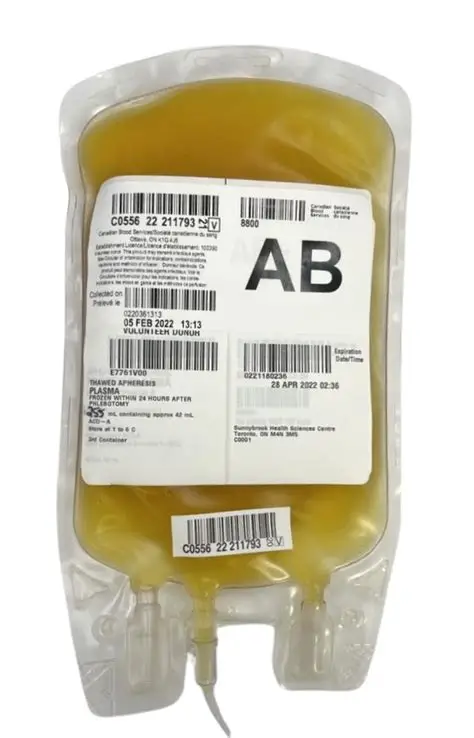

Therapeutic approaches to hemophilia have evolved dramatically over the past century. Early management relied on whole blood or plasma transfusions, offering limited and short-lived benefit. The introduction of plasma-derived factor concentrates in the mid-twentieth century revolutionized care by allowing targeted replacement therapy. However, these products carried risks of viral transmission, leading to devastating outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C among hemophilia patients in the 1970s and 1980s. This tragedy spurred advances in blood safety, viral inactivation, and ultimately the development of recombinant clotting factors.

The Now: Modern Treatment Strategies

Current management of hemophilia centers on factor replacement therapy, administered either on demand to treat bleeding episodes or prophylactically to prevent them. Prophylactic regimens, particularly when initiated in childhood, have been shown to dramatically reduce bleeding frequency and preserve joint function. A significant complication of therapy is the development of inhibitors, neutralizing antibodies that render replacement factors ineffective. Management of inhibitor-positive patients requires bypassing agents or immune tolerance induction, both of which add complexity and cost to care.

The Future: Emerging Therapies

Recent decades have seen the introduction of novel non-factor therapies that rebalance coagulation by targeting natural anticoagulant pathways. These agents offer the advantages of subcutaneous administration and reduced bleeding rates, even in patients with inhibitors. Gene therapy represents a particularly promising frontier, aiming to provide long-term or potentially curative correction through delivery of functional clotting factor genes. While challenges remain regarding durability, immune response, and access, these therapies signal a profound shift in how hemophilia may be managed in the future.

Hemophilia as a Model for Translational Medicine

Hemophilia occupies a unique place in medical history as one of the first genetic disorders to be understood and effectively treated through targeted replacement therapy. Its study has driven advances in genetics, immunology, transfusion medicine, and biotechnology. For clinicians, hemophilia exemplifies the importance of integrating pathophysiology with patient-centered care. For informed lay readers, it illustrates how a single molecular defect can shape lives, families, and entire fields of medicine, while also demonstrating the capacity of scientific progress to transform once-fatal conditions into manageable chronic diseases.

Comments